Every so often, a piece of writing hits with such quiet force that it stays with you long after the last word. This is one of those pieces. It’s rooted in the emotional truths many of us navigate in silence. I’m honored to share this guest post by Stew Sheen, a friend and fellow traveler in the in-between spaces.

What follows is unsettling. Beautiful. Devastating. Read it slowly.

I never wanted to be the one to speak up.

The thought alone made my stomach turn. But what was I supposed to do? Sit there while my husband, a respected yungerman, sat across from me at the kitchen table and told me he didn’t believe Hashem ever spoke to the nevi’im?

I turned off the faucet and let the last bit of water drain from the fleishig sink. I could still hear his voice from last night - steady, measured, as if he were discussing a Tosafos and not denying the very foundation of our emunah.

"I was learning with Moshe today," he said, breaking a piece off his roll. "And I realized something. I don’t think Hashem ever actually spoke to the nevi’im. I think they wrote their words based on what they felt, what they believed."

I remember the way my fingers tightened around my spoon. "Yehuda," I whispered, eyes darting toward the window. "You can’t say things like that."

He sighed, leaning forward like he was trying to help me see it. "Rivka, I keep Shabbos. I learn every day. I just—this is the emes. I can’t pretend to believe something I don’t."

My stomach churned. This wasn’t a childish doubt or some fleeting question. This was kefirah. And once words like that leave your mouth, they don’t just disappear.

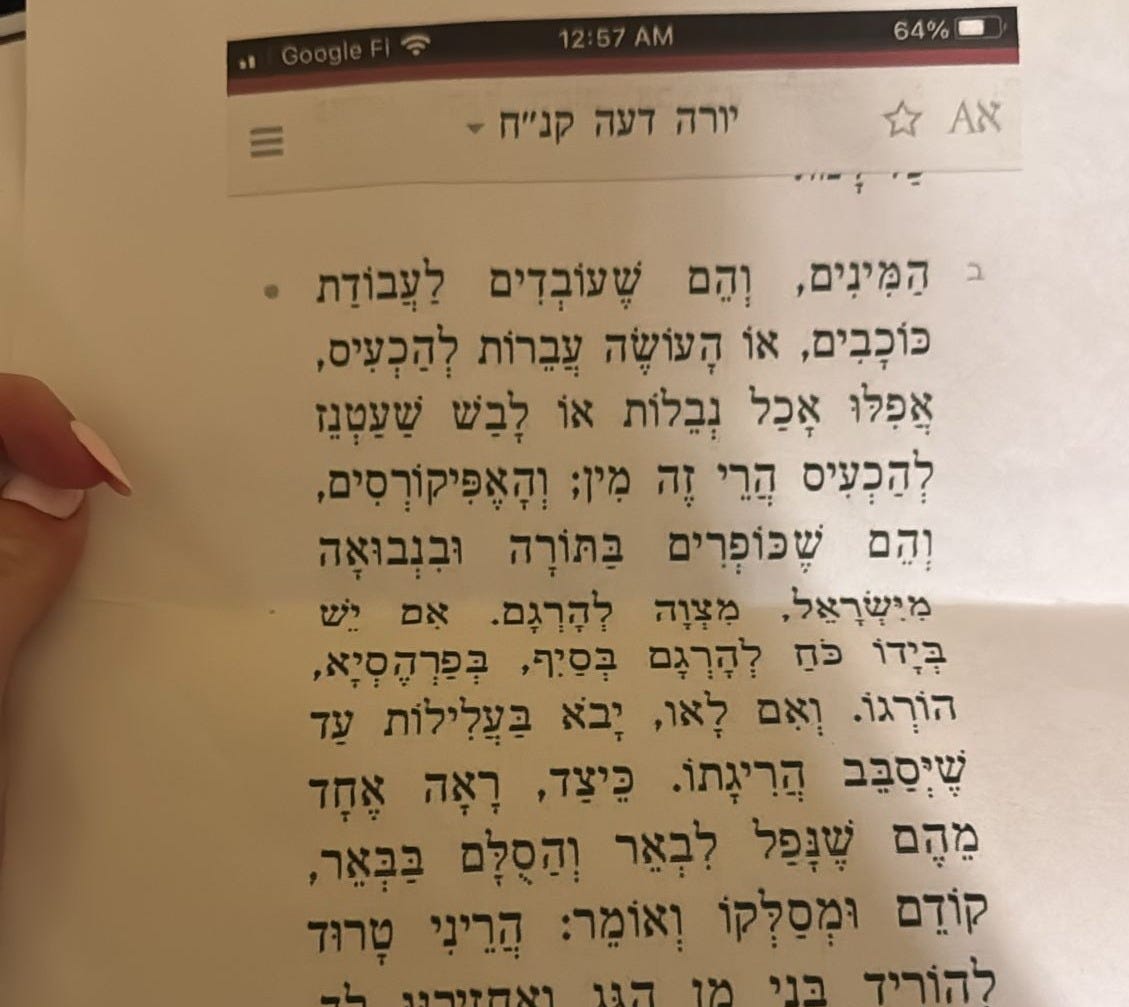

I barely slept that night. What was I supposed to do? Pretend I hadn’t heard him? Let him go on learning in the beis medrash like everything was fine? I knew the halacha. Someone who denies Torah mi’Shamayim isn’t just making a mistake. They’re a danger to Klal Yisrael. And in our town, where every psak followed the Shulchan Aruch to the letter, there were consequences.

By the time the sun rose, my mind was made up. My hands trembled as I knocked on the door of the Beis Din. When I was called in, I couldn’t meet the Rav’s eyes.

"Rebbetzin," he said gently. "What brings you here?"

I opened my mouth, but the words caught in my throat. I forced myself to think of our children. What would happen if they heard their father say such things? What if others did? Slowly, I told him everything.

The summons came before Mincha. Yehuda was taken into the Beis Din. I wasn’t allowed inside. I stood outside, davening, trembling, waiting. The streets were quieter than usual, word spreading faster than I could have imagined. When the door finally opened, Yehuda’s face was pale but calm.

"You told them," he said. There was no anger, just a quiet sort of resignation.

"I had to," I whispered.

The psak was swift. The halacha was clear. A kofer who publicly denies Torah mi’Shamayim is chayav misah. And in our kehilla, where we had the power to enforce it, the Beis Din didn’t hesitate.

That night, they let me see him one last time. He was sitting in a small, dimly lit room in the Beis Din. He didn’t look scared. If anything, he looked… relieved.

"Why didn’t you just take it back?" I pleaded. "Why didn’t you just say you were mistaken?"

He gave me a faint smile. "Because it wouldn’t be emes," he said.

I wanted to scream at him. To shake him. To make him understand what he was doing to us. To me. But it was too late.

The kehillah gathered in the empty lot behind the beis medrash. Two dayanim read the psak aloud. Yehuda stood in the center, his hands bound, his kittel ghostly white. The first stone struck his shoulder. He stumbled but did not cry out. The second caught him in the ribs. By the third, he was on his knees. By the fourth, he was gone.

I remind myself that daas Torah knows best. That the Beis Din follows halacha. That this is what the Torah demands. I tell myself that Yehuda was sick. That his mind had been confused. That he brought this on himself. That the world makes sense. That everything is as it should be.

I tell myself these things, over and over and over—

until they settle deep in my bones,

until the storm inside me quiets,

until all that remains is emes.

The interesting thing is that most Orthodox Jews do NOT REALLY BELIEVE that these punishments are real. They are very skilled in compartmentalizing the aspects of Judaism that are enjoyable and neutral, and the barbaric components such as these.

It is not possible to live a functional life while simultaneously believing all the awful consequences of hundreds of actions, non-actions, thoughts and lack of certain thoughts.

Well written so sad :/